Nine Months of App Dating

Last summer, having recently gone through a breakup and with no real-life romantic prospects to speak of, I turned to dating apps. My prior experiences with app dating, which were minimal, were also mildly painful—full of palpable awkwardness and the persistent impression that I didn’t know what I was doing.

It wasn’t imposter syndrome; I didn’t know what I was doing.

I’m convinced that the world of dating strangers is defined by an ambiguous and unique set of rules and expectations that differ significantly from the norms for all other human relationships. I also believed that, just as humans can learn to do basically anything, I could learn to navigate romantic relationships with people I’d met through electronic devices operating according to artificial intelligence. I could learn to app date.

I was planning to apply to grad school this past cycle, so I knew it was likely that I would be moving to a new city a little over a year after I started dating. What was I looking for on the apps? To blunder my way through every social faux pas and painful silence on the path to whatever relative confidence or ease might be waiting on the other side. And if I met someone I liked in the meantime, great! Hopefully I just wouldn’t like them enough that it would be devastating when I moved away. The logic was flawed, I’ll admit.

Dating Like a Scientist

Dating sort of scared me. There’s no way to avoid getting rejected and rejecting others. Eek. Treating dating like a science experiment helped keep things in perspective; I could be driven by curiosity to understand myself, other people, and this particular social phenomenon instead of the hope for any particular outcome.

For the 9 months that I was actively app dating, I recorded some basic data on the experience. I was using the app Hinge.1 I dated starting last summer and stopped a few months ago when I knew for sure that I was moving away. Now I’m analyzing the data set, hoping to gain some insights I can apply if I return to the apps in my new city after starting grad school.

App Dating Basics

In case you’re not a millennial/gen Z and have no idea what Hinge is, here are the basics: you create a profile with photos and responses to prompts, then the app shows you other people you might be interested in and you decide whether or not to “like” each of those people (I refer to this process as “swiping”). When one person “likes” another person’s profile, the other person gets a notification and can decide whether or not to match with that person. If you match with someone, you can send messages back and forth.

The Data

You can think of app dating as a series of decisions along a prescriptive path. At every stage, you and the other person decide whether or not to continue down the path.

Here’s how I defined that path and the stages along it to use in my data set:

- Initial like - Person 1 is shown person 2’s profile and person 1 decides whether or not to “like” person 2.

- Like Response - Person 2 gets the “like” and decides whether or not to match with person 1.

- First message - Either person could send a message to the other.

- Message response - The other person could respond.

- Ask out - One person could ask the other to meet up in person.

- Date 1 - They might meet up in person for the first time.

- Ask out 2 - Someone indicates interest in seeing each other again.

- Date 2 - They go out a second time.

- Date 3, etc. - They go on a third date, fourth date, etc.

During this 9-month study, I recorded:

- The people whose profiles I was shown and whether or not I “liked” them.

- The people who “liked” me and whether or not I chose to match with them.

- For the people I matched with, how far along the above stages we got, and who initiated for the stages where one person initiates (i.e. who “liked” whose profile first, who sent the first message, who asked the other out, etc.).

Note that the data set here is incomplete. Since people can “unmatch” with prior matches or delete their profile, I definitely missed some people who were no longer showing up as matches when I periodically went through my matches and wrote down the progression of stages. (I will also admit to doing some swiping without writing down every decision).

My intentions going in

To me, part of dating like a scientist meant reviewing the literature and applying what was already known about how to date successfully. Logan Ury’s How to Not Die Alone provided a great overview and I tried to apply a lot of the recommendations she shares in the book. I also reviewed some of my other favorite scientific takes on dating and love, such as Joanne Davila’s TEDTalk and Amy Webb’s TEDTalk.

Here are a few of the intentions I had when I started:

Be open-minded about potential matches. Ury emphasizes being open-minded when deciding who to “like”/match with. Basically, check yourself for being overly judgmental and question the “rules” you might have set about who you would or would not be interested in.

Message the people I match with. I think it’s generally pointless to match with someone and then not message them. I like to tell myself that either I’m interested or I’m not interested in someone and if I’m interested I should match and message them.

Get through the messaging and to the meeting in person stage. I find the messaging stage generally tedious and tiresome. I regularly forget to text back people I already know and like(link to sorry post), and adding strangers to that mix doesn’t make it any easier. Messaging feels like a necessary step to demonstrate that you’re interested enough in the other person to put in some effort and build the minimal amount of trust you need to meet up with someone, but not especially valuable in figuring out how much you might like the other person. Thus, my intention was to ask out and/or go out with most of the people I matched with, besides those who never messaged or stopped responding to messages before we could set something up.

Results: My Likes

I’ve always been uncertain about who to “like” on dating apps. You can blame my social psych background; I know way too much about stereotypes, prejudice, and cognitive heuristics not to question all my opinions. The advice from the literature to be open-minded caused me to be even more indecisive.

I find myself asking the same two big questions whenever I swipe: Are my initial judgments about people based on their profiles good predictors of how much I would like a person in real life/how likely they are to be a good partner for me? If I don’t just take my immediate judgments at face value, how am I supposed to choose who to “like”?

More on potential answers to these questions later. For now, here’s the swipe data:

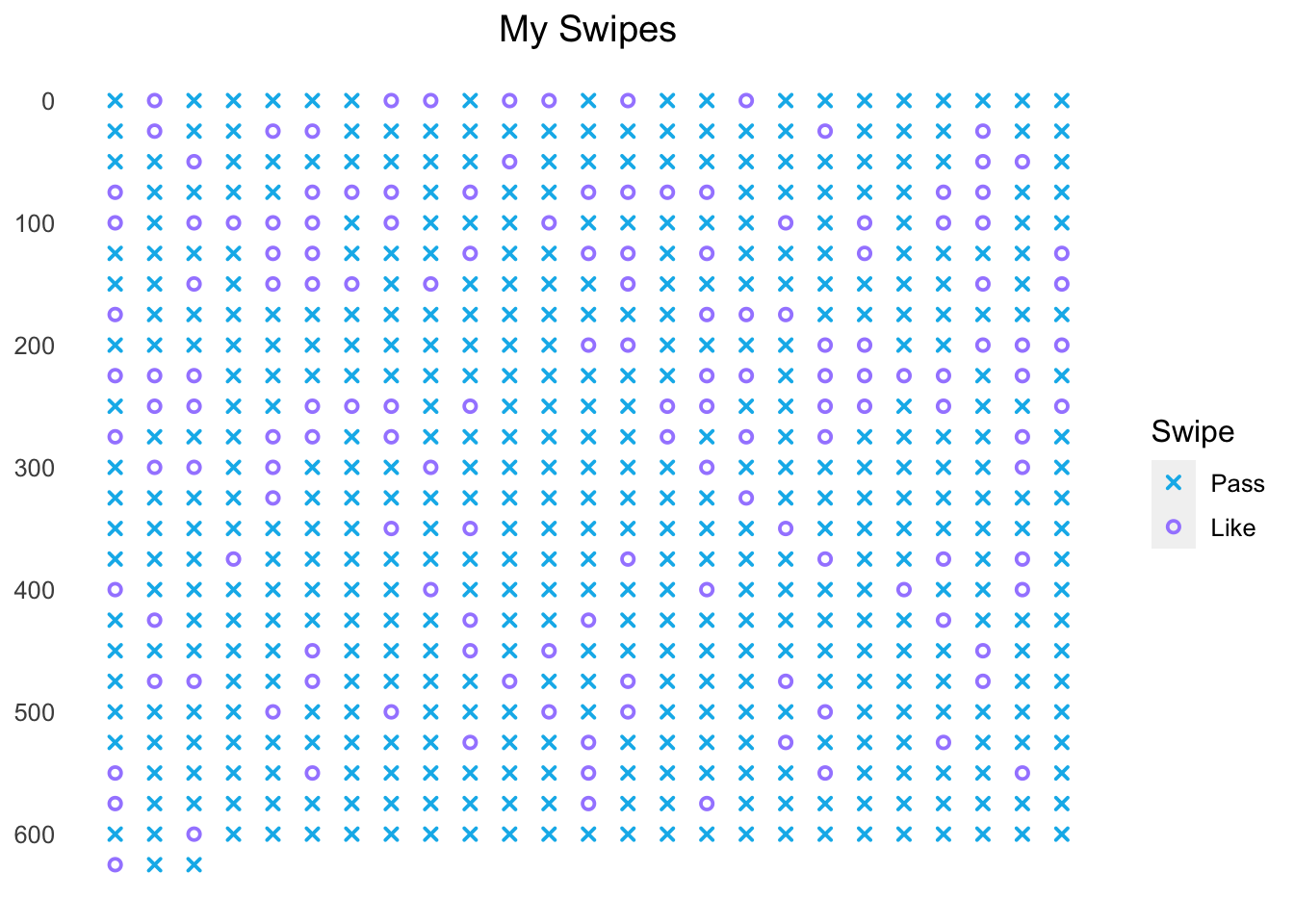

Here’s a visualization showing the people I swiped on and whether or not I chose to “like” them. The swipes are shown in order from top left to bottom right, with 25 swipes in each row.

I recorded 628 swipes and I “liked” 150 of those people, for a 24% “like” rate.

I also looked into whether my “like” rate changed over time. The following graph shows my average “like” rate for the last 50 swipes across the 628 swipes I recorded in total.

The second half of the swipes, my “like” rate was much lower than the first half. During the first half, there’s a striking dip in the middle before my rate rises again. My like rate is presumably a function of both match quality and my leniency with sending out likes. It looks like I became less lenient over time.

One specific struggle I had was around whether to “like” people who displayed a lot of outdoorsy/athletic content on their profiles. My impression is that, among queer women in Boston, there’s a strong norm in favor of being athletic and outdoorsy. Climbing, hiking, farming, and backpacking photos were everywhere on the profiles I was being shown.

As a person who likes being outside but has less access to outdoor activities than many other people because I am disabled, the tone around outdoor activities sometimes feels judgemental, like people who can’t or don’t do those things are being looked down upon. But I can’t always tell, am I being unfairly judged, or am I the one doing the unfair judging? I never came to any lasting conclusions.

People who Liked me: My “Like” Responses

Responding to people who “liked” me felt like a more worthwhile place to practice being open-minded than those who hadn’t yet expressed interest in me—I was more likely to actually meet them and be able to evaluate whether the open-minded strategy was worthwhile.

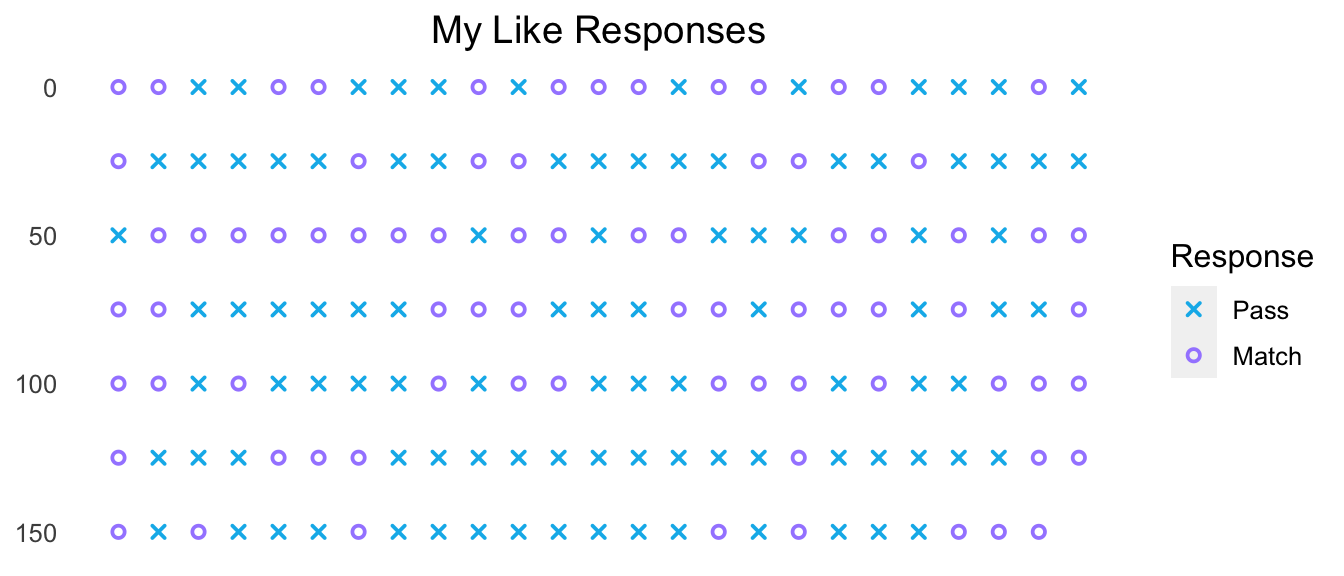

So, I matched with a lot of people I wasn’t particularly excited about. Here are my responses to people who “liked” me:

I responded to 174 “likes” and matched with 77 of them, for a 44% overall match rate. For each profile I was shown, I was almost twice as likely to match with someone who had “liked” me than I was to “like” someone initially. I was much more lenient with matching than initial “liking”.

Stages Reached Among Matches

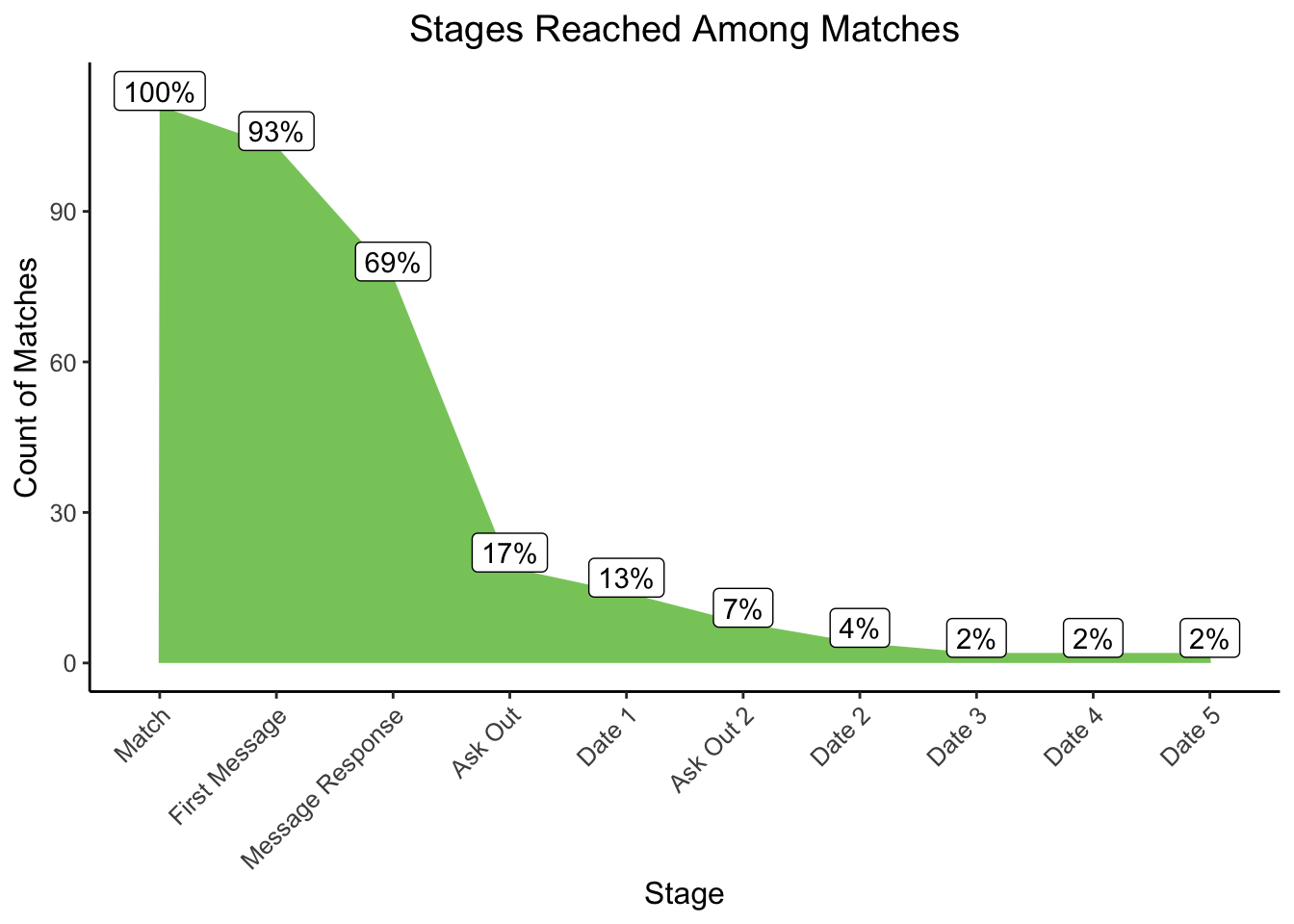

Now onto the data I was most interested in: among people I matched with, how far did we get along the stages I listed above?

I matched with 111 people during the 9 months. The latest stage I got to was a fifth date, which I went on with 2 people. Among all the matches, the labels show the percent of matches that got to each stage. I ended up going on a first date with only 13% of matches (about 1 in every 8 matches).

I did a decent job sending an initial message (93% of the time at least one of us sent a message), but there’s a huge drop-off between message response (69%) and asking someone out/being asked out (17%). Messaging is the treacherous abyss where potential relationships go to die. The data paints a pretty clear picture: I didn’t do a good job getting through the messaging stages with matches and onto the date stages, which was one of my main intentions. The small number of dates compared to matches wasn’t an intentional choice that some people weren’t worth going on dates with; it was the product of carelessness in maintaining the conversation long enough to plan to meet in person.

I didn’t record data on how many messages were sent, the time in between messages, or who ultimately stopped responding, but I can tell you that I deserve significant blame for the 69% to 17% dropoff. I avoided responding to messages. I got overwhelmed. I got bored. I regularly disappeared for long enough that the conversations lost momentum. Many of the people I matched with were doing the same thing; I got a lot of “sorry I disappeared for 2 weeks!” messages.

I can’t change other people’s behavior, but I can change mine. If I go back to app dating, I vow to respond to messages approximately every day.

I also looked into whether there were different outcomes for the people I initially “liked” compared with those who “liked” me first (where I was much more lenient in accepting matches).

I was slightly more likely to get to the ask out, date 1, and ask out 2 stages with people who liked me first and who I matched with than with people I liked first who matched with me, though these differences are not statistically significant. This could be interpreted as a sign that being open-minded about who to match with was worthwhile, but I think it’s just as likely that any differences here are a reflection of my commitment to follow through on going on a few dates with people I matched with, and so the instances where the other person had liked me first, and thus was potentially more invested, led to more dates than when I was the more invested party. I wasn’t going on any more third dates with people who liked me first than with people I liked first.

If I continued with the same behavior, for every 1,000 people I swipe through, I should expect to “like” 239 people, match with 57 people, message and receive a response from 35 people, ask out/be asked out by 8 people, go on a first date with 5 people, and a second date with 2 people. During that time, I could expect to receive 277 “likes”, match with 119 of those people, message and receive a response from 88 people, ask out/be asked out by 22 people, go on a first date with 18 people, and go on a second date with 5 people. But of course, I do plan to change my behavior.

Take-Aways

After analyzing this data, it’s clear where I should make a few changes.

First, I need to follow-through on responding to messages more promptly and consistently. That’ll be achievable if I have fewer matches and I’m more excited about those matches. Based on my informal observation, I generally liked the people I was more excited about based on their profiles when we actually went on dates. There was tons of variation, but a positive trend emerged. Perhaps my being more excited about someone was what caused the dates to go better, but I doubt that explains the entire effect. When done well, I think a dating app profile does give some indication of the kind of person someone is and the kinds of things they like and care about, and those things matter in how much I like people.

I felt largely indifferent about a lot of people I saw on the apps, but there was the occasional person I really wanted to meet. I’d like to spend a larger proportion of the time and energy I put into dating on those people. So, I’m going to raise the bar for a “like” or match. I will try to retain some of the open-mindedness by checking myself on the judgements I am making about people, but matching with people I don’t actually want to talk to or meet does no one any favors, especially if it’s preventing me from actually meeting up with the people who could have been better matches. I am hoping I will start to figure out when it makes sense to be open-minded and when to trust my (judgy) gut. Maybe I’ll be able to differentiate decisions based on different emotions, and perhaps I could amplify the decisions driven by curiosity instead of, say, guilt.

Hopefully, not questioning my opinions so much will also help teach the algorithm what I’m really looking for.

I also think I should do a better job following the advice from the literature to go on second dates with most people I go on first dates with. According to the data set, I went on 14 first dates (an undercount, I am sure), and I swiped through 628 age- and geographically-appropriate queer women (although, some were duplicates). I have dated enough people I’ve met in real life to feel confident that there must have been people I saw on the app that I would have liked and dated for more than 5 dates in the right circumstances. First dates with someone you met on an app just aren’t those ideal circumstances. I should take that to heart and be more willing to meet up with people I felt “enh” about for a second time. That, too, will be more doable if I have fewer matches and I am more interested in them.

Based on my reflections, I also hope to be more persistent about seeing people I like but potentially am only interested in platonically. I feel a lot of pressure when going on dates (often with the expectations of more and more overtly romantic contexts) with someone about whom my feelings are approximately, “you’re cool, but is this friendship?” There was someone I really liked who I went on 2 dates with and neither of us suggested a third. I felt like we totally could have been (and were on our way to being) friends, so I only saw her twice and then never followed up with her (although, I did run into her later on the subway). Now I look back and think, given my obvious affection for her, how was I so sure friendship was our destination? There has to be a better way to navigate this uncertainty than bailing and never seeing the person again.

Other Things I Learned

After these 9 months of app dating, I have some opinions:

- First dates should be 1 hour. Even good dates are exhausting. An hour is plenty of time to get to know someone a little, but not so long that your conversations aren’t going anywhere anymore even if you like the person. New dates are valuable resets. I tend to worry that my date will think the effort and prep required of the date weren’t worth it for an hour-long date, so I like to set the expectation that the date won’t be much longer than an hour before we meet. Then, our expectations are aligned and my date knows it’s not a negative reflection on them when I say I should head out 60 minutes into our conversation. I have friends who will say they’re free “from 6-7pm” when they’re arranging the date. I like to suggest meeting somewhere an hour and 15 minutes before the place closes, and mentioning the closing time when we’re making a plan.

- The perfect first date plan is hard to orchestrate. I want to learn the basics about my date on the first date, so we need a chance to talk one-on-one. I don’t want the pressure and awkwardness of talking being the only thing the two of us are doing. I don’t want to spend much money or have to put in a lot of preparation or be in either of our homes. It’s a lot to ask for. Some of my go-to optimal first date ideas are to meet somewhere outside and paint (frivolous and low-quality) watercolor paintings together, to meet at a café where there’s a jigsaw puzzle we can work on to pretend there aren’t any moments when we just have no idea what to say, or to meet somewhere and walk to and from some kind of (ideally free and relatively brief) event together.

- Dating is one of those rare things that is both scary and boring (sometimes simultaneously). We deserve all the self-compassion.

Conclusion

Much as the final results demonstrate obvious room for improvement, and much as I am still just as single as I was a year ago, I also see some big wins here. I floundered my way through many awkward moments. I was rejected. I rejected others. And here I am, feeling more sure of myself and slightly more engaged with the (puzzling, painful, and circuitous) human experience.

And hey, maybe sometime soon I’ll go on a sixth date.

P.S. As usual, here’s a link to see my code.

P.P.S. If you would like to receive an email when I publish a new post, please fill out this google form.

I also did some other forms of dating, such as going to in-person Skip the Small Talk events, which I would highly recommend to anyone living in a city where that’s available, but I only collected data from Hinge.↩︎