72 Potential Lies: Results of My 6-month Honesty Audit

One evening a few years ago at my old apartment in Boston, I broke one of our drinking glasses. It wasn’t exactly an honest mistake; I was being careless. The glass was behind me full of water while I was reading on the couch. When I reached back to grab it, I knocked it onto the floor where it shattered. I considered texting my roommates to tell them I broke one of our glasses, but I decided not to say anything.

A month or two later, we were getting ready to host a party. My roommate started walking around trying to find all the glasses, saying, “I really thought we had more.” She searched. I said nothing. Then she asked me directly: “do you know if any glasses have broken recently?”

That’s when I lied: “not that I know of.”

Intro to Honesty

A podcast episode sparked my recent fascination with honesty. The episode was an interview with a psychiatrist who talked about how her patients who make the greatest strides in recovery from addiction have rigorous and profound relationships to honesty. The psychiatrist hypothesized that unwavering honesty is necessary for recovery. Science has yet to confirm if or why honesty and recovery might be so intrinsically linked, but her theory piqued my interest nonetheless. I started to wonder how strictly I held myself accountable to the truth.

I decided to start tracking every time I lied.

My research question quickly evolved as a few things became evident. First, knowing that I was keeping track of any lies I told made it impossible to “act naturally.” There was no way to measure if I would have lied had I not been trying to keep track of lies. Second, I tend to be pretty careful to not lie. I value honesty and I can generally see right through my own bullshit, so there wouldn’t have been many actual lies to log. At least, this is what I’d like to believe. And third, it’s hard to draw a clear line between lies and not lies. Is hyperbole lying? Is exaggeration? How do you differentiate between simplification and oversimplification? Which lies are so socially conventional they shouldn’t count?

We lie to conceal the truth. However, we can often still conceal something without having to lie about it. I realized tracking the urge to conceal would provide a more objective and insightful data set than tracking actual lies. So, I began collecting data on times I felt even a slight urge to conceal something, whether or not I yielded to that urge.

The urge to conceal was accompanied by a very specific cognitive process which I became adept at recognizing: if I felt at all inclined to lie about something, I would begin to construct an alternate story. The story didn’t have to be elaborate. When my roommate was trying to find the missing drinking glasses, my alternate story was simple: I had no idea what happened to the missing glasses.

A few weeks ago, when my mom was talking to me in the car and I was nodding along with my mind somewhere else completely, I didn’t explicitly lie to her. But I was acting in accordance with a story that wasn’t true, and that story was “I am totally listening to what you’re saying.” Those moments of pretending were what I started tracking. I also tracked moments when I considered pretending, but didn’t – like when I hesitated before getting a second slice of pizza at a pizza party (story: I am completely satisfied by this one slice of pizza).

Data Collection

I logged potential lies for 6 months, and in that time I recorded 72 potential lies.

At first when I started tracking times I wanted to lie, I was horrified. The little sparks of shame or fear of judgment were frequent and incessant, flickering to life during conversations with my roommates, phone calls with my parents, and even therapy sessions. They were everywhere. Were my everyday interactions nothing more than a series of confrontations with realities I wanted to deny?

I don’t think I would have been ready to track my urges to lie if I hadn’t gone through a bout of serious depression a few years ago; the experience radically altered my self-compassion. Perhaps it was my perpetual inability to meet my expectations for myself during the worst of the depression – the only way forward was to be so much kinder to myself. I feel like I finally got the hang of self-compassion, and I relied on it heavily during data collection for this post. I got through my initial disappointed surprise at how often I wanted to lie, and I was able to continue data collection from a place of (mostly) nonjudgmental curiosity.

Since I decided the urge to lie was more measurable and meaningful than actual lies, for the rest of this post I’ll be discussing those urges without differentiating between whether or not I lied in response.

Unspeakable

There’s this song I quite like, “Why am I like this?” by Orla Gartland (thanks, Heartstopper, for the great soundtrack). There’s a line in the bridge I find myself pondering sometimes: “Let’s go out and shout the words we never said.” I like the thought experiment. What if one day we all just decided we were wrong about everything we’d judged unsuitable for being said out loud?

This study is something along those lines. I wanted to know what things I, at least momentarily and at least in a particular time and space, judged unsayable. Here’s what I found.

Results

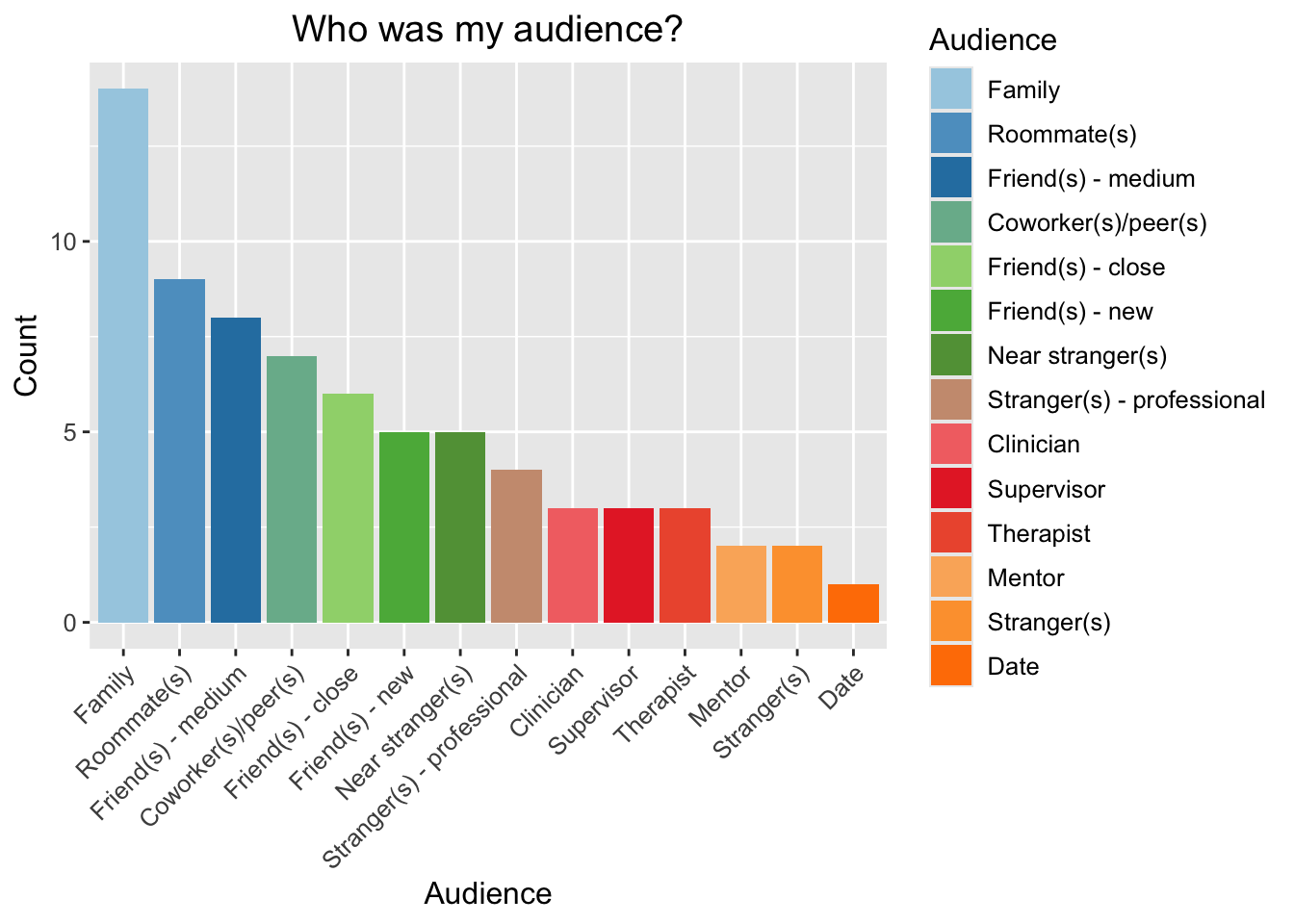

For each potential lie, I coded who it was I was talking to. Here are the results:

My most frequent audience was my family followed by roommates, and my least frequent audience was someone I was on a date with. Of course, I haven’t accounted for how much time I spent interacting with each of these groups, so there’s no way to calculate the frequency of wanting to lie when interacting with each group. I’ll discuss these findings and what I think they mean more later.

Emblematic Features

I spent a lot of time trying to categorize the potential lies in my data set, but there were so many correlated dimensions, categorizing was confusing and hard. So, instead I’m going to illustrate some of the major features of the potential lies by describing a potential lie to illustrate each feature. The features are not mutually exclusive, so the same potential lie could display multiple features.

The “I’m not proud of what I did” Lie

Perhaps the most classic lie is the “I’m not proud of what I did” lie.

In the first few weeks after moving to Maryland to start my PhD, the WiFi went down in my house. The router happened to be in my room. I noticed the WiFi was down but didn’t feel like dealing with it, so I did little to troubleshoot the problem. This was inconsiderate because a few of my roommates were new to the US and didn’t yet have cellular data, so they relied heavily on the WiFi. Some time after the WiFi went down, one of my roommates approached me to ask about it, and I wanted to pretend I hadn’t noticed it was down to hide the fact that I knew but hadn’t tried to fix it.

This illustrates an interesting feature of the “I’m not proud of what I did” lie: often, the things I wasn’t proud of were smaller than I might have guessed. I wouldn’t have predicted I’d want to lie about my actions until the moment it was time to own up to them.

The “I don’t want to hurt you” Lie

Getting ready to move to Maryland, I found a house I wanted to live in and then talked with other people looking for housing to decide who to invite to be roommates. When I spoke with someone interested in joining the house but I didn’t want to live with them, I always hesitated to tell them the truth.

I really dislike potentially hurting people. Not avoiding these conversations is something I’m working on. For me, lies in this category vary in how much wanting to lie is really about not wanting to hurt someone else versus not wanting to personally experience the discomfort of rejecting someone. Lies to avoid hard conversations, broadly speaking, form a very large category of potential lies for me and, I suspect, other people.

Variations of the “I don’t want to hurt you” lie include the “I don’t want to make you feel some other vaguely negative emotion” lie, like the time I went out to dinner with a group of people I didn’t know very well and ordered a meal it turned out I didn’t like. I wanted to lie about it, I think because I didn’t want to dampen everyone else’s evening by letting them know I didn’t like my food.

The Smile and Nod Lie

Adjacent to the “I’ll lie to make you feel good instead of bad” category is the smile and nod lie. The smile and nod lie is specific to microaggressions and other insults disguised as compliments.

Many months ago, one of the other presenters came up to me after I’d given a presentation in an informal setting. I had never spoken to him before. He opened the conversation with something like, “I’m so glad you presented.” Then he said, “you’re really into it!” It struck me as backhanded and immensely condescending. I said, “thank you” and smiled like he’d given me an excellent compliment, then walked away rolling my eyes.

Part of me wishes I’d said something to him, like, “that feels really condescending,” instead of faking it. Whether or not I’d do things differently if I could relive it, one thing I feel strongly about is the fact that I didn’t owe him anything. Not my smile, not my thank you, not my composed education about the impact of his words.

The “I’m Afraid of this Conversation” Lie

One of my roommates wasn’t home in time for the house meeting we’d scheduled. When she arrived very late, I was frustrated with her but wanted to pretend I wasn’t frustrated.

This is different from the “I don’t want to hurt you” lie because I wasn’t worried about my roommate’s feelings, I was worried about our relationship and whether acknowledging a rupture, however small, would derail our fledgling friendship. I was afraid of the conversation the truth would necessitate.

The Feared All-or-Nothing Conclusion Lie

Often, the specific truth wasn’t so scary, but it was accompanied by the fear that the audience might conclude something broader based on this truth. Let’s return to the example of me wanting to get another slice of pizza at a work pizza party. There was plenty of pizza left, but so far no one had gotten more than one slice. It wasn’t that I didn’t want my coworkers to know I’d eat two slices of pizza, I was afraid they would extrapolate based on that instance to conclude that I was gluttonous. (I know I said I wouldn’t tell you whether I actually lied or not, but I can’t pass up this opportunity to brag. I did get a second slice of pizza, and many others followed suit. Please, hold your applause.)

In most instances when I wanted to lie, I was partially avoiding some possible global conclusion about me or the other person that might be made based on the interaction. I coded these feared all-or-nothing conclusions. In 56 of the 72 potential lies, there was a relevant all-or-nothing conclusion. Although, the feared all-or-nothing conclusion wasn’t necessarily the primary motivation behind wanting to lie.

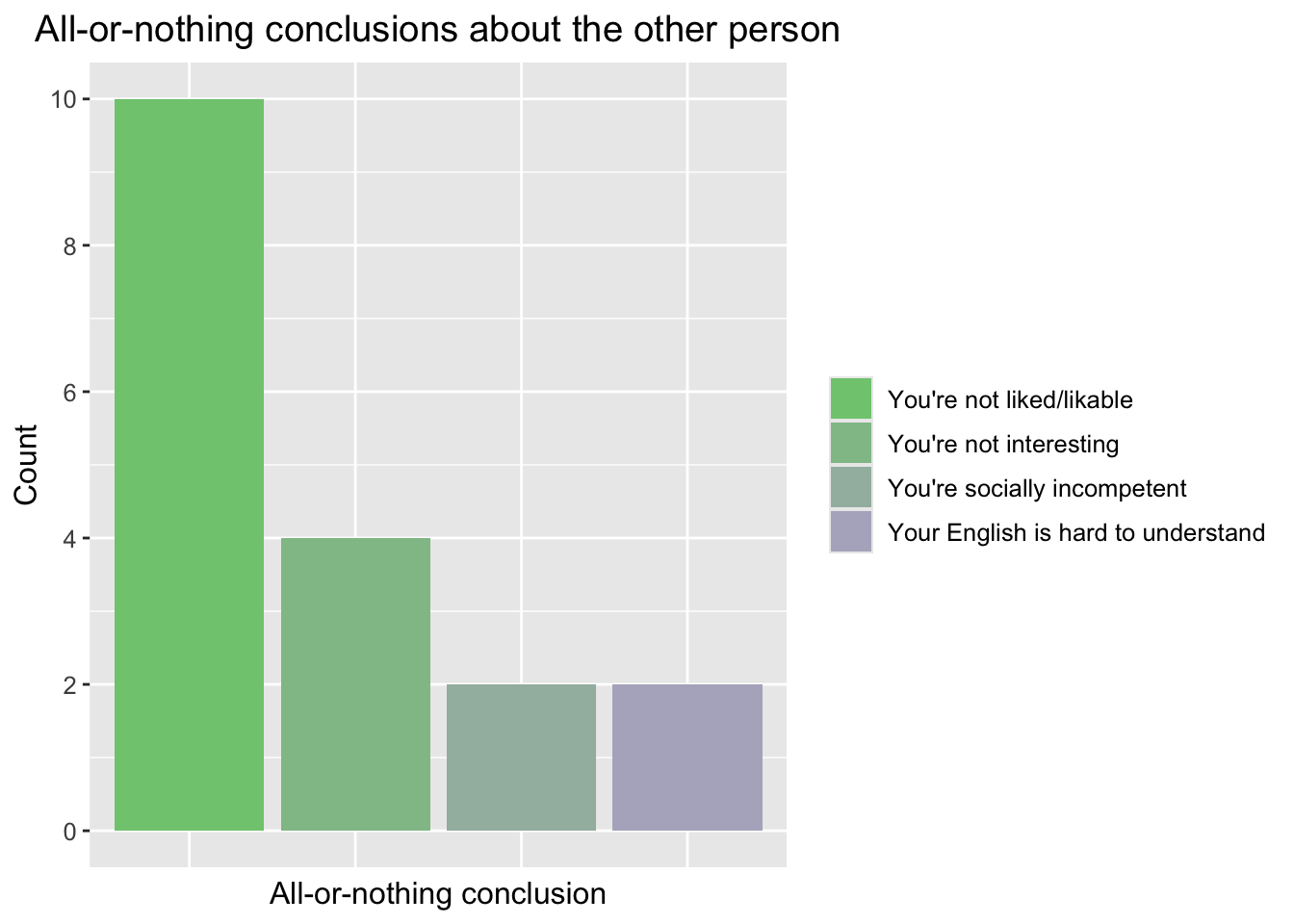

Here are the all-or-nothing conclusions about the other person and the number of times they came up:

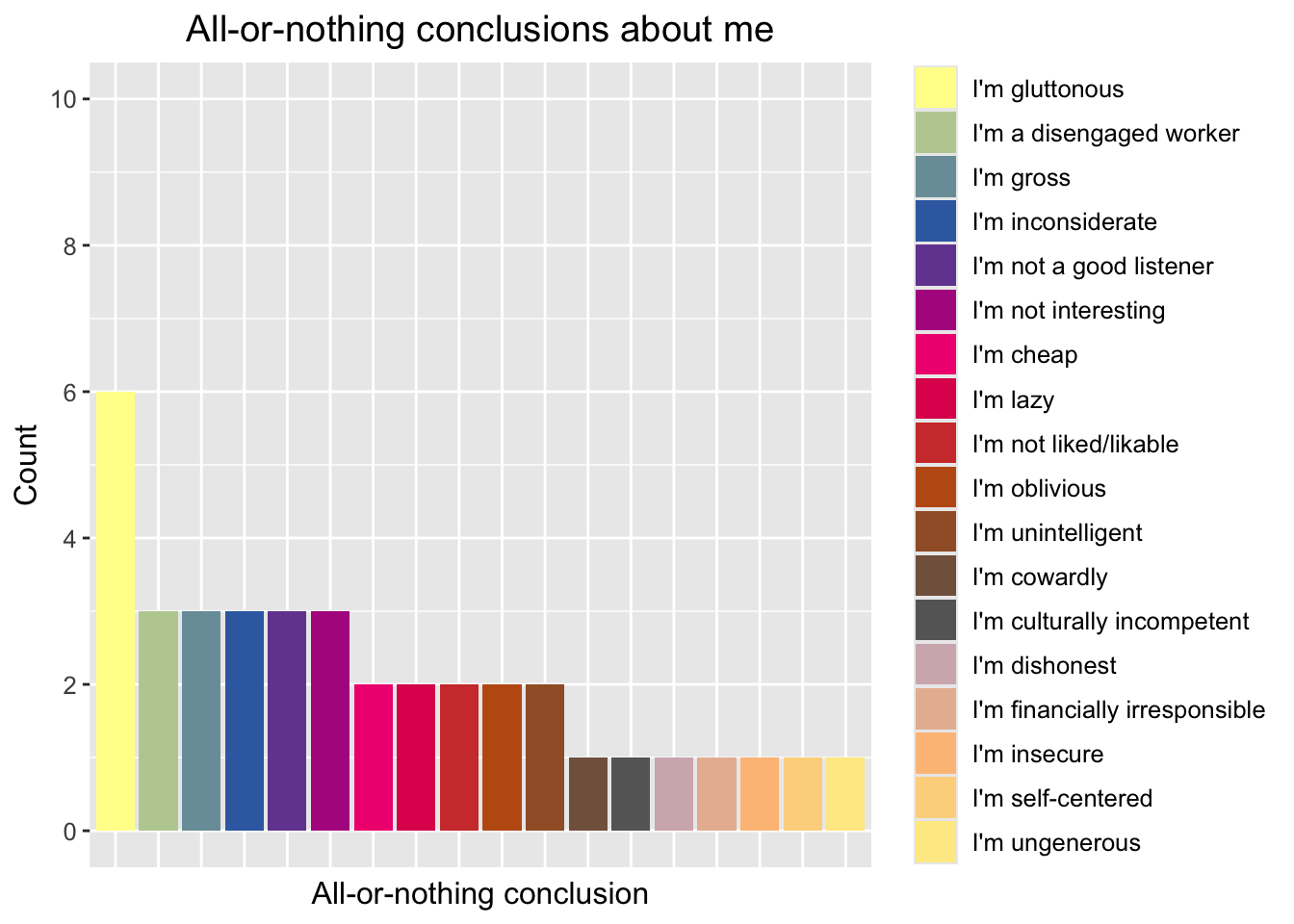

And here are the all-or-nothing conclusions about me:

The all-or-nothing conclusions about other people were much less varied than the conclusions about me. I was most frequently afraid to make other people feel not liked/likable or not interesting. Being liked and being interesting strike me as pretty basic and broadly applicable human motivations, so it makes sense that I was hesitant to say anything that might call into question these characteristics.

Compared to the 4 all-or-nothing conclusions about other people, 18 unique all-or-nothing conclusions about me came up.

I was most frequently afraid to be perceived as gluttonous. I could write a whole post about women and eating. Here, I’ll just say that, for women, I can think of few labels more stigmatizing than “gluttonous.” I don’t think it’s the thing I’m most afraid of so much as the thing I most frequently feel pressured to perform maintenance in avoidance of. When being perceived as gluttonous was on the line, I hesitated before doing what I wanted to do. And being perceived as gluttonous often felt like it was on the line.

I look at this list of 18 all-or-nothing conclusions about me and it strikes me how much there is to be afraid of. I think there are certain socially unacceptable traits that we’re trained to be in constant maintenance against, and this list enumerates some of them. It’s also striking how much the 7 deadly sins make appearances.

I think the list of different conclusions about me is so much longer than the list of different conclusions about other people because there are only so many attributes that are essentially based on someone else’s perceptions of you. The four conclusions about other people, “you’re not likeable,” “you’re not interesting,” “you’re socially incompetent,” and “your English is hard to understand,” are about traits that are inherently relational. My impression holds much more weight about whether someone else’s English is hard to understand than it is about whether they’re, say, athletic. There’s nothing I could confess to someone that would make them conclude that they’re not athletic in the way that admitting to not understanding what someone is saying to me could impact their impression of their English.

Meanwhile, there’s no limitation on things I could admit to having said or done or thought that would make people conclude a variety of negative things about me.

In moments when there was an all-or-nothing conclusion at stake, whether I decided to tell the truth depended largely on my relationship to that particular conclusion. There were some conclusions I could confidently reject, and thus could embrace the related truths. Being unintelligent is a good example of that. I love the way I think and it’s enough for me, so I’m generally not afraid of other people concluding that I’m unintelligent. Once I realized this, I started openly expressing moments of bewilderment or confusion.

A few months ago I was on a first date and I mentioned that my friend recently moved to Switzerland, to Zurich specifically. Then I suddenly had a terrified moment in which I thought, “wait, Zurich is in Switzerland, right?” Since I no longer believe in faking it so other people don’t think I’m stupid, I had this thought out loud. My date was also not entirely sure if Zurich is in Switzerland. It is, by the way, but I wouldn’t blame you if you momentarily confuse Zurich with Munich. It’s a very understandable mistake.

There were other conclusions I could see some truth in. “I’m not a good listener” is one. The all-or-nothing conclusion is still a distortion, but it’s also true that I could be a better listener. Finding myself wanting to lie about having not really listened to someone, I realized I also wanted to start listening better. My parents were usually the audience I was faking it about listening to, and they deserve better.

The “I don’t want to look at it” lie

I think often we lie to maintain distance from things we don’t want to look at directly.

Last year, a friend invited me to a gathering she was hosting for Purim and I didn’t want to go. I wanted to lie and tell her I already had plans so I wouldn’t have to admit I just didn’t want to attend her gathering. I couldn’t acknowledge that I didn’t want to go to her gathering without also acknowledging that we hadn’t really been friends for a while, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue trying to revive the relationship. I wasn’t ready to face all that, so I wanted to pretend we existed in an alternate reality where I simply had other plans.

I lied about breaking the drinking glass for similar reasons. I had once been very close with those roommates, but things had gotten more and more complicated and difficult. I couldn’t text my roommates admitting to breaking a glass without acknowledging how little grace it felt there remained between us, so I didn’t tell them. Then, it was a slippery slope to lying when my roommate asked me about it directly.

I’m sure it won’t come as a surprise to you that lying isn’t something we reserve for other people. We lie to ourselves, too. I couldn’t measure it the way I could measure wanting to lie to other people, but looking back on the lies I wanted to tell, it’s clear that sometimes I was the person I most wanted to hide things from. When we don’t want to face the truth about something, we lie to other people, too.

Is the truth so bad?

Is the truth so bad? That’s the question I started asking in the moment after realizing I wanted to lie about something. Identifying the truth was the first step in answering that question. Here’s a list of some of the truths I found myself wanting to conceal:

- I can’t use chopsticks very well

- I can’t figure out how to edit the PDF

- I didn’t understand the joke even though it was an obvious one

- I don’t get what you’re talking about

- I don’t want to go to your thing

- I don’t want to live with you

- I felt complicated about seeing you

- I found your comment really condescending

- I frequently consume chocolate

- I have money but don’t want to give it to you

- I knew the WiFi was down but didn’t really try to fix it

- I put in lots of effort to see you

- I want more pizza

- I want more water

- I haven’t started that work project yet

- I thought many more people might come to this party

- Not knowing how to pronounce Louisville makes me so uncomfortable I avoid using the word

- I invited you to this out of a sense of obligation but I hoped you wouldn’t come

- I am frustrated with you

- I’m not listening

- I’m mad at you

- You just got my name wrong

- I’m definitely going to be late and it’s my fault

- I want to lick the spoon

- I don’t really garden

The truth is not so bad.

In many cases, it was obvious as soon as I identified the truth I was hesitating to share that the truth was just not so bad.

Here’s an example: I was out at a ramen restaurant with a new friend. When the server brought our ramen, he asked if either of us wanted a fork to use (we already had chopsticks). I wanted a fork, but didn’t want to admit to wanting a fork. It became a little joke in my head, imagining myself dramatically confessing. “I know we don’t know each other very well, but there’s something I need to admit. I’m not great with chopsticks.” It’s just ridiculous.

There were so many moments like that. Things that I felt initially hesitant to reveal actually just made for vaguely vulnerable social exchanges. In general, a lot of the things I wanted to lie about were really quite small. I think that often, naming exactly what you’re afraid of makes it seem much less scary.

The truth is moderately bad.

Navigating truths that could hurt others is still really hard for me. Even when the rejections are small, like telling near-strangers I don’t want to be their future roommate, I avoid them. But I realized it’s not less painful or demoralizing to just never hear back from someone than it is to be told directly that they don’t think you’re a good match as roommates. When you don’t say something, you make it more unspeakable.

One thing this study made me face is the fact that we can’t get away with never hurting other people. If I have to inflict hurt, I’d rather it be clear, honest hurt than vague, confused hurt.

The truth is unbearable.

Sometimes, in the more challenging moments of my life, I find myself brushing up against the very edges of the potential realities that feel bearable. I brush up against them, and then it hurts too much and so I turn away. I wrote above about how the truth is not so bad. But sometimes, it is so bad.

Sometimes you love someone and they don’t love you back. Sometimes a dear friend stops being a dear friend, or you’re surrounded by people who don’t really see you, or you’ve made a mistake and you can’t repair the damage. Where it’s possible not to see such truths, we often choose not to see them. Maybe lying is all about trying to spare ourselves and each other from such huge and excruciating heartbreaks.

Some realities are awful. Some truths are unbearable. Yet, whether we look at them directly or not, the truths are the truths. They’re not all-or-nothing. They’re more complicated and, often, more devastating than the lies and the partial-truths we tell. I think that is one of the central undertakings of personhood, to try to expand that scope of realities that we can bear to look at, or live in. When we turn away, to muster all our strength, and turn back. I’m working on turning back.

The Place for Lies

I’m a big fan of honesty and authenticity, even when telling the truth is hard. However, I also believe that lies have their place. Dishonesty of various forms is a part of our everyday lives and it’s not necessarily desirable or possible to eradicate entirely.

Sometimes, lying is necessary to protect someone else’s privacy or safety. For example, I’m perfectly comfortable lying to not out someone who doesn’t want to be outed. Sometimes we also have to lie to preserve our own privacy or safety.

There are social conventions that encourage, if not outright lies, then overstatements. Take for example the “I don’t want to leave but I have to” script we’re often expected to adhere to when leaving a social gathering (e.g. “I should get going; I’ve got an early morning tomorrow.”). Nobody says, “this was fun but I am ready to be alone now” on their way out of a dinner party.

The dating app Hinge has a “typical Sunday” prompt. I would not recommend responding to it with your actual typical Sunday. Nobody who’s deciding whether they want to date me needs to know I spend many Sunday afternoons lying sideways on my couch, reading research articles in harried preparation for my meeting with my graduate advisor the next day, and eating Ritz crackers straight from the sleeve. Instead of taking the prompt literally, I’ve responded to the unwritten prompt “describe a Sunday that illustrates things you like to do while also showcasing your best qualities.”

My personal favorite lie is the lie as resistance. At the Indianapolis Public Library, the staff are always trying to keep unhoused people from washing their clothes in the bathroom sinks. The library staff apparently don’t want to actually go in the bathroom and kick people out, so they ask people coming out of the bathrooms to report on other patrons. My mom goes to the library regularly, and when leaving the bathroom, if a staff member asks if anyone was in there washing clothes, my mom looks at them with slight confusion and then says, “no.”

On Faking It

I think sometimes it’s okay for our internal experience of something to be different from our external experience of it, but it also can be hard. Some kinds of faking it wear away at you, interaction after interaction. The larger the discrepancy between what you’re saying and your genuine experience, the worse it feels. For example, I find that it usually feels fine to say, “I’m good” in response to “how are you?” but every once in a while when I’m going through something especially hard, it can feel awful.

We’re not all asked to fake it in equal measure. Depending on what your experience is, expressing that experience authentically might be welcomed or might come with terrible consequences. We as a society make different amounts of space for the expression of different experiences. We do a terrible job making space for things we don’t like or know how to talk about like grief. We don’t make room for identities that aren’t especially visible in society, like immigrant and refugee experiences. I also feel this about being disabled/chronically ill— I don’t always feel like I get to talk about it. And the existence of stereotypes can add to the risk involved with authentic expression, such that people with marginalized identities feel the need to avoid seeming to fulfill harmful stereotypes about their social groups.

I think part of how we harm people with marginalized identities is by making authenticity riskier and faking it more necessary.

On Authenticity

So, total authenticity all the time isn’t how we live, but I think we all need people with whom we can be really truly real.

Here’s the basic case for honesty: honesty requires vulnerability and authenticity. Vulnerability and authenticity are critical in the formation of close relationships. Close relationships are integral to wellbeing.

It occurs to me, this whole list of times I wanted to lie was also a list of vulnerable moments. Wanting to conceal is one flavor of feeling afraid. At their core, interactions involve vulnerability. There’s no way around it. So, in some ways, our everyday interactions are a series of confrontations with realities we want to deny. I think nonjudgmentally seeing ourselves as we are and others as they are, terrifying as that may be, is one of our kindest and most meaningful human endeavors. I hope you find the courage, grace, and space for a little more of that, as I did through this project.

P.S. As usual, here’s a link to see my code.

P.P.S. If you would like to receive an email when I publish a new post, please fill out this google form.